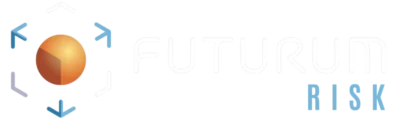

Inside the Network: What Southeast Asia’s Cybercrime Compounds Reveal About Modern Organised Crime

In 2025, cybercrime no longer looks like a lone hacker behind a screen. It looks like a guarded building on the outskirts of Phnom Penh. A maze of dormitories, computer labs, confiscated passports, and forced labour. This is not a vision of the future; it is the current architecture of organised cybercrime in Southeast Asia.

Last week, members of the Futurum Risk team, Richard King and Dominic Diaz Sizer, attended a table talk at Hong Kong’s Foreign Correspondents’ Club (FCC), titled “Inside Southeast Asia’s Cybercrime Compounds: A Survivor’s Perspective.” The session revolved around Scam, a newly released book by Ivan Franceschini and Ling Li, which documents the emergence of hundreds of scam compounds across the region. These sites operate as modern digital sweatshops, where the victims of trafficking are often coerced into becoming perpetrators of large-scale fraud.

Dominic Diaz Sizer, Futurum’s Strategic Advisor in Hong Kong, reflected on the experience:

“Attending the Book Talk for Scam at the FCC this week was a valuable opportunity to engage directly with authors Ivan Franceschini and Ling Li. Their work shines a crucial light on the hidden realities of Southeast Asia’s cybercrime compounds and the resilience of survivors. It’s inspiring to see such dedication toward addressing these complex issues and supporting those affected by organised crime.”

The book launch reinforced what many intelligence professionals already suspect: the future of crime is structured, cross-border, and increasingly difficult to detect.

The Corporate Evolution of Cybercrime

What the authors describe, and what survivors confirm, is the industrial scale of digital exploitation. These are not temporary operations. They are permanent compounds, equipped with trained supervisors, shift schedules, performance targets, and disciplinary systems. They mimic legitimate business process outsourcing (BPO) models, but are built on the back of human suffering.

Inside, trafficked workers are trained to conduct crypto fraud, online investment scams, sextortion, and “pig butchering” romance scams. They are often recruited under false pretences and then locked inside, forced to scam others under threat of violence.

The compound model allows criminal networks to concentrate operations, improve efficiency, and protect leadership from exposure. It is organised crime in a new format, structured, digital, and disturbingly scalable.

The Real Risk: When Exploitation Becomes Infrastructure

For those of us in risk analysis and intelligence, these developments raise urgent questions:

- How do we detect exploitation when it is disguised as economic activity?

- How do we anticipate threats when they are no longer mobile or ad hoc, but infrastructure-based?

- And perhaps most importantly: what signals are we ignoring?

Many organisations continue to assess risk through siloed frameworks, treating financial crime, trafficking, cyber threats, and geopolitical stability as separate. But the compounds exposed in Scam prove that these risks converge. And when they do, the damage is far-reaching: not just financial, but ethical, reputational, and operational.

“The emergence of cybercrime compounds in Southeast Asia is a reminder that organised crime is evolving faster than many realise. Our approach at Futurum Risk is to integrate diverse intelligence streams, combining digital forensics, human networks, and open-source data, to build a comprehensive understanding of these hidden ecosystems. Only by seeing the full picture can we help organisations anticipate risks before they escalate and respond with precision.”- Richard King, Lead Intelligence, HK

Jurisdictional Confidence Is a Mirage

A core theme from the FCC table talk was how easily these compounds can emerge and remain hidden in regions with weak oversight and ambiguous law enforcement. Countries like Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos have become hotspots. But the model is portable. It can be exported to any jurisdiction where corruption, infrastructure, and plausible deniability coexist.

This challenges the notion that operating in a “regulated” environment is enough. The reality is that criminal economies thrive on legal grey zones, and by the time risk registers formally, via sanctions, travel advisories, or media exposure, the structure is already deeply embedded.

For international businesses, NGOs, and financial institutions, that’s a dangerous lag.

The Intelligence Imperative: Connect the Dots Sooner

At Futurum Risk, we don’t view risk as a checklist. We view it as a pattern. And what’s happening in Southeast Asia is not an anomaly; it’s a case study of what happens when too many dots are ignored for too long.

Some of the earliest indicators of compound activity weren’t hidden:

- Job adverts targeting vulnerable populations: Thousands of fake recruitment listings began appearing online, often promising tech jobs or customer service roles in Southeast Asia. These were disproportionately aimed at young workers in economically distressed regions, especially in Africa, South Asia, and rural China, offering salaries far above local averages and requiring minimal qualifications. The language was vague, but the bait was effective.

- Consistent social media patterns tied to trafficking: Across platforms like Telegram, Facebook, and TikTok, recurring narratives emerged, people posting about “amazing overseas opportunities” followed by sudden silence or cries for help. Survivor stories, once dismissed as isolated, started aligning across different regions, showing clear patterns of deception, control, and transport into restricted compounds.

- Investment fraud spikes traced to specific geographies: Financial institutions and cyber teams began noticing waves of complaints about fraudulent crypto schemes, fake investment platforms, and romance scams. IP tracing often pointed back to the same cluster of locations: border towns in Cambodia, special economic zones in Laos, and newly developed tech parks in Myanmar, each becoming hubs for digital exploitation.

- Shifts in power consumption and telecom usage in semi-rural zones: Utility data and mobile traffic patterns showed anomalous activity in areas previously considered low-risk. Sudden spikes in electricity use, SIM card purchases, and data traffic suggested the rapid build-up of infrastructure. These subtle signals were often dismissed as economic growth or construction, until it became clear that many of these sites housed cybercrime compounds.

Each signal on its own is easy to miss. But when layered together, they reveal an operational footprint. That’s where private intelligence adds value, not in reaction, but in recognition.

Understanding the Economics of Cybercrime Compounds

To truly grasp the resilience of these operations, it’s important to understand the economics behind them. Scam compounds aren’t just criminal ventures; they’re profit engines, often generating millions of dollars per month in stolen funds. The model is low-cost, high-yield, and surprisingly scalable. Labour is trafficked rather than hired. Infrastructure is often secured through corruption or complicity. And digital fraud allows proceeds to be laundered instantly through cryptocurrency or third-party financial fronts.

This combination of cheap labour, decentralised tools, and weak regulation creates the perfect storm. For criminal networks, it’s not just sustainable, it’s replicable. For risk professionals, this raises a critical point: the problem isn’t going away. It’s expanding wherever the economic model is allowed to take root.

Closing the Gap Between Insight and Action

The FCC event reinforced what many of us in the intelligence field already know: understanding risk isn’t just about data, it’s about narrative clarity. When you hear directly from survivors, when you see the inner workings of these compounds described in detail, it becomes impossible to unsee the systemic design behind modern crime.

Southeast Asia’s cybercrime compounds are not outliers. They are prototypes.

As these models evolve, the real question becomes: will institutions keep looking at threats in isolation, or will they start mapping risk like a network?

At Futurum Risk, we’ll continue to engage with frontline insights, listen to the stories, and refine our methodologies. Because staying ahead doesn’t start with software. It starts with seeing the structure before others do.